Target audience

If you want to reach developers, you need to understand them. It's not about showing cool features or tossing around buzzwords - it's about knowing how developers live and think. Developers, Economic Buyers, all see the world a little differently, and each has a real influence on what tools and technologies succeed inside an organization. Respect how they work and speak their language, and you have their attention.

01

Personas

A persona is a fictional character that represents the typical attributes, mindsets and behaviors of a certain group of people. Personas target audience research, and are best used for building empathy and understanding, as well as reality checks for better marketing decisions.

Economic Buyer

The Economic Buyer (EB) is the key person who ultimately decides whether money is spent or not. They have the organizational authority, trust, and responsibility to make purchasing decisions for new tools, frameworks, and services. Although they may not physically approve the invoice, their word usually seals the deal. From the brand perspective, they are the ship's officer making sure the crew has the right equipment — while balancing against the ship's overall operating costs.

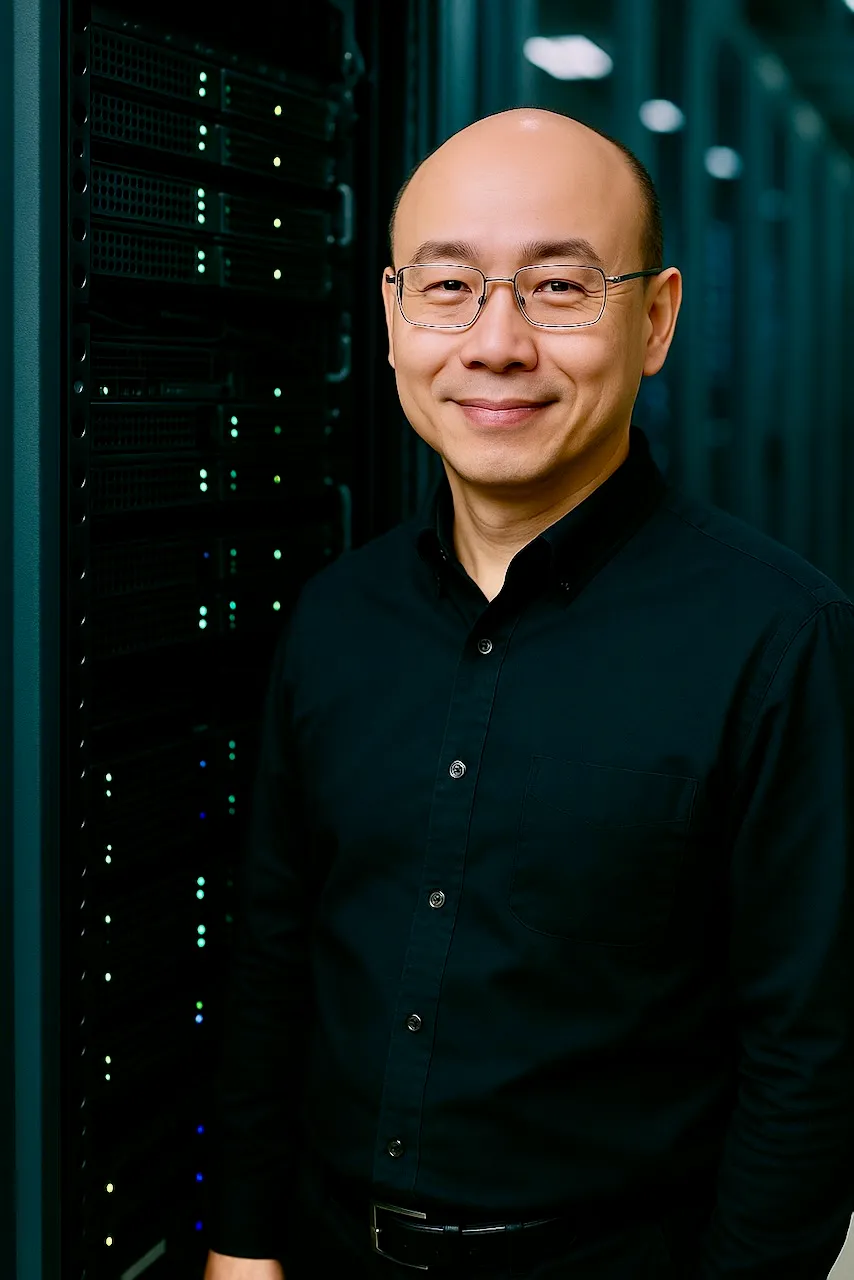

Technical background, leadership role

Most Economic Buyers come from a technical background — they were developers once and understand technology deeply. Today, they are in leadership roles like CTO, VP of Engineering, Director of Software Development, or similar. They are no longer hands-on coding, but they still think like engineers and take pride in their technical competence. Dumbing down messaging for them might be perceived as insulting. They expect discussions to be technical, strategic, and financially grounded.

Accountable for strategic technical decisions

The EB is responsible for ensuring that the technologies chosen today will support the organization’s needs tomorrow. They think long-term about the cost of maintaining systems, team skillsets, technical debt, and the speed of delivering features to customers. While they might delegate the exploration and evaluation of new tools to senior developers or architects, they make the final call on whether the team should invest time and money into adopting something new.

Budget control and business alignment

Economic Buyers often control the engineering budget — or at least have significant influence over it. They may need to seek final approval from a CEO, CFO, or procurement department for larger purchases, but typically they shape and lead the budget request process. They think not just about licensing costs, but also the hidden costs of adoption: training, migration, support, maintenance, and long-term viability.

EBs live at the intersection of technology and business. They constantly balance competing priorities: keeping developers happy and productive, delivering projects on time, maintaining technical quality, and aligning engineering work with company goals. They think about value delivered over time — not just today’s velocity.

Works through the team

Economic Buyers rarely make unilateral decisions on new technology. Instead, they listen to recommendations from trusted technical leads and thought leaders inside the team. A successful technology purchase usually follows a bottom-up path: the team identifies a need, experiments with possible solutions, validates their effectiveness, and then brings a strong case to the EB.

However, if the team fails to advocate convincingly, or if the EB senses hidden risks (vendor lock-in, scalability issues, unclear ROI), they will veto or delay the purchase. The EB’s ultimate loyalty is to the organization's long-term success — not to the wishes of individual developers.

Focus on long-term impact

While developers focus on short-term productivity, Economic Buyers worry about long-term consequences. They are cautious about adopting flashy new tools that could create maintenance nightmares down the line. They prioritize sustainability: clean architecture, manageable systems, realistic roadmaps, and predictable costs. They need to feel confident that any technology adopted today will not become a liability tomorrow.

Thought Leaders

Respected in their team

Thought Leaders are highly skilled developers. They have typically worked in their organizations for years, but are almost never C-level. Their contributions are critical, and they always have their organization's best interests in mind.

Product adoption

Thought Leaders are relatively active in discovering, researching and sharing insights about interesting new technologies, both within their organization and on external platforms. Their relationship with a product might be a brief trial before moving on, or they might become long-term champions of the product inside their organization.

Thought leaders are the ones who find us, let's optimize discovery for them.

Long-term vision

Thought Leaders know their organization's processes and technologies inside out. Thus, they can consider the impact of any technological change on their organization in a holistic manner. Any core technology needs to endure time and remain in production even 10 years from now. They need to be supported so that security and other issues won't become their team's burden eventually.

Fears

Thought Leaders fear of advocating, or becoming responsible for a technology that leads to a development dead-end, stuck with an abandoned and unmaintained technology, endless maintenance work, and eventually an expensive migration of products to a new technology.

Developers

Normal every day Developers make the majority of any developer brand's target audience. They are the silent majority, and the main workforce that gets stuff done. Crunching through sprint backlogs one issue at a time, coding new features, enhancements, bug fixes. From the brand perspective they are the ship's crew that must be kept content, or otherwise they will organize a mutiny.

Let's serve these developers well and humbly!

Professional developers

A typical developer works in a dev team with other professional developers. Although they might aspire to be a Thought Leader in the future, today they are not calling the shots. They might not have time to be learning new skills or trying new technologies on the daily basis.

Participates in product adoption

All developers share their opinions about any technologies they come across with their colleagues. They might not all suggest new technologies to the team, but they can block the adoption if they have a poor experience using it. They might participate in the evaluation process or prototyping with the rest of the team, comparing frameworks, scoring findings, etc. Often, their needs can be easy to satisfy: provide good documentation and enough learning materials.

Works with the tools provided

On average, developers are not very actively looking for new tools or technologies to try out due to demands of their current project. They might not be up to date on latest development trends, and sometimes even 5 years behind on current trends. They are willing (or forced) to work with whatever tools their team or organization decides to use, and if the tools work, they'll keep coding away until someone brings in a new set of tools.

Productivity = Resolved issues

While it might not be reasonably, developer's performance is often seen through the number of resolved issues in a sprint. Quality is sometimes negotiable, as long as things get done. UX might not be that high in their priorities, and it might be unclear what even makes a good user experience beyond a logically structured UI.

Focus on the short-term

Early in their careers, developers are often still finding their place. In their work, they tend to not think for the long-term consequences of their choices, and focus on short-term goals and getting things done. There's some fear and avoidance of wasting time in long, elaborate solutions, which might be thrown away and kill your velocity.

Other developer types

The Jaded Developer

Jaded developers are typically in senior positions, such as lead developers and architects, with over a decade of experience from many projects. They've burned themselves in the past with technologies that made too lofty promises of benefits that turned out to be unsustainable. They are skeptical towards any bold claims and understand there are no silver bullets. They require hard proof, in-depth materials and first-hand validation before they accept something as a fact. But after validating your claims they can become your strongest advocate in their organization.

The Crafter Developer

"Why would I use your product when I can do this project just the way I like it with my favorite technologies, frameworks, libraries and tools?" Crafters avoid opinionated products and platforms, where decisions have been made for them beforehand. It's not just a matter of opinion - some might feel superior to developers who just assemble web apps from ready-made components. Crafters take their time to maintain their skills and professional value, so accepting someone else's opinions would be devaluating your own skils.

The Student Developer

Even though professional developers should be the main target audience of any commercial brand, it's important to acknowledge students - tomorrow's professional devs - as well. Students appreciate simplicity, great documentation and lots of learning resources for every skill level.

02

The mindset

Software developers are a very heterogenous group hard to capture in a sentence. It's better to paint a larger picture and approach the topic from multiple angles.

Basic demographics

Full-stack, back-end, front-end developers; architects

25-45 years old, predominantly male

5-15 years of professional developer experience

Education and learning

Software development is constantly changing with new languages, technologies and tools. Keeping up with the progress is essential for professional developers and their organizations. Although roughly 2/3 of software developers have a Bachelor's or Master's degree, most skills are still learned through online resources and on the job.

For online learning, developers clearly prefer technical documentation, such as APIs and other comprehensive formats. More verbose formats, such as tutorials, how-tos, blog posts and videos are also popular. Online platforms such as YouTube, Stack Overflow, Stack Exchange and Reddit, and many technology-specific Discord channels are appreciated for their insightful responses and communal spirit.

Another learning and face-to-face meeting opportunity are the various developer events, where companies and communities gather together around a topic. These events can be split into two main categories: big and small events. A big, high-profile enterprise conference focuses on companies meeting customers, has industry-leading keynote speakers, and typically attracts people from the top part of organization charts. A smaller conference or event is typically community driven, has a tighter focus in speakers and sessions, and due to lower ticket prices and travel costs, attracts developers from more junior roles.

Developer communities

Perhaps to counter-balance all those moments of solitude while being in the zone, developers also seek social connections. We prefer informal ways, both asynchronous and synchronous, to share our experiences, troubleshoot hairy problems, and learn new things. One of our core insights tells us that a technical problem can be solved just by describing it to someone else, so we see very concrete benefits in being social.

Developers hang out in communities. The most well-defined ones are formally organized, have clear boundaries, memberships, platforms and spaces, moderation. Typically there are some sort of organizations putting considerable effort behind them. Some examples are Stack Overflow, GitHub organizations, or company-backed Discord servers.

Semi-structured communities are loose un-organizations around a shared interest, e.g. a tool, technology or profession . Participation is optional and fluid - if you use a framework, contribute to an ecosystem, or live in the area of a local meetup group, you're in. No one is usually putting too much effort into getting things organized beyond a little push here and there.

The third kind of developer community is the most elusive one. Communities that form organically around an interest or e.g. a project may not even self-identify themselves as communities. Boundaries, memberships, platforms and interactions are all very loosely defined.

Developer communities tend to be highly meritocratic and specific. A positive reputation and authority is built purely on contributions. Demonstrated technical expertise, quality code commits, helpful behavior, taking the time to solve others' problems, ability to teach and explain complex topics etc. are the kind of actions that increase your status and reputation. Job titles and other external attributes tend to have diminishing importance.

Community x Brand guidelines

Always be developer first

Representing company and product must come second

Contribute value

Offer honest insights and solutions beyond your own product scope

Be authentic

Real developers' voices, genuine tech talk, transparency, no hype.

Help the community grow

Support knowledge exchange, recognize contributions.

Developer marketing

"Developers and marketing are like water and oil - they just don't mix"

Actually, that stereotype isn't the full truth. Developers, like anyone else, would love to learn about new products that could make their work better, and that's the core function of marketing. There's just so much marketing. Developers are the primary targets in most tech products' bottom-up sales approaches. It's safe to say there's always someone, somewhere, sifting through their data, identifying new developers, preparing their next marketing activity.

Marketing activities aren't categorically bad. It's the badly done marketing that's bad. It used to be super simple to spot bad marketing from afar: hyperbolic statements, mental images instead of facts, fake sales guys who had no idea what they were saying etc.

Nowadays, marketing has become systematic and ubiquitous, powered by basic tracking mechanisms. Cookies and pixels, form submissions, email opens, website visits - all feed into marketing automation platforms that trigger endless waves of "personalized" outreach. A developer who downloads one whitepaper suddenly finds themselves in dozens of drip campaigns. Their LinkedIn profile gets scraped and matched to contact Their casual visit to a product page leads to weeks of retargeted ads following them around the web.

In theory, these tools should be marketing precision weapons. The problem is, the tools are wielded like shotguns - blast enough developers with enough messages and surely some will convert. The same generic "Developer Resources" emails flood inboxes. The same 'personalized' ads show irrelevant products. The same sales sequences march on regardless of response. It's marketing by volume rather than value.

This automated assault has trained developers to be extremely wary. One wrong click could expose them to months of unwanted outreach. So they arm themselves with ad blockers, temporary emails, VPNs, privacy-focused browsers - anything to stay off marketing's radar and out of its automated sequences.

This is the reality bad marketers and good marketers share today. A good brand with good marketing needs to reach developers even stronger and clearer than all the rest. That's why it's critical to know your audience intimately, and tune your messaging and activities to be developer-friendly.

Developer marketing guidelines

#1 Developer first

Be authentic and transparent. It's easier to trust messages from a real person with a name and a face. Content written by developers to developers have also much higher engagement rate. Respect the time and personal details developers have given to you. Offer swag or show other acts of gratitude when appropriate.

Don't try to bypass developers' needs or step on them like a stepping stone to reach decision makers with commercial offering. Don't trick developers with "Contact Us" buttons that will place them on a sales team hit list. If someone wishes to have a meeting with you and spend an hour of their time, it's immediately suspicious - what do they expect to have in return for their time.

#2 Don't push - Let them pull

Developers are turned off by sugar coated materials and websites with too much whitespace, and become skeptical of promises without concrete proof. Give them a GitHub repo they can clone and experiment with to reach the same conclusions on their own.

Avoid bad marketing automation. It's tone deaf and untimely, and tells developers they are not respected or recognized as who they are, but as faceless leads in a marketing automation sequence. Be very aware of each developer's progress with your product. Don't push on with more features, trials or commercial offerings just after registration – developers are not ready to consider such things so early. Don't try to skip developer's needs and reach out to their decision maker too soon.

Allow developers to ask for more when they're ready. Offer opportunities to join Q&A sessions, weekly onboarding group sessions or other events that will happen regardless of their personal attendance. Offer a reply possibility to onboarding emails, e.g. "If you have any questions, reply to this email and ask away, Sami from our team will get back to you with an answer". When developers have the initiative, and they feel there's no target painted in their backs, they can relax.

#3 Don't sell - Help them sell

Due to the prevalence of bad marketing, even the faintest signals, like a careless choice of words, can tip the interpretation of your message from developer-relevant to sales-irrelevant. Facing commercial messages too soon or just in the wrong place in the journey will lead the developers into thinking they will need to sales just around the corner. As a consequence, many will drop off.

If a developer is not in acute need of a tool, or otherwise motivated to explore new tools, it will be very difficult to get them invest their time in evaluating your product beyond a few clicks. It might take several starts and restarts to get them really started. Before that semi-serious evaluation journey has been completed, it's highly unlikely they would connect your sales team with their decision maker.

Developers need to feel the excitement and satisfaction from using your product before they are ready for anything else. When they want to use your product, they want to tell others about it and become your brand advocates inside their organizations. This would be the right time to point them towards extensive materials tailored for their decision makers. When this approach is done right, they will ask you to contact their Economic Buyer, not the other way around.